Foot Binding: The Painful Practice Of Chinese Lotus Feet

Could a practice that involved breaking and contorting the feet of young girls be considered a form of beauty? For centuries in China, the answer was a resounding yes, as foot binding, a custom of inflicting severe pain and permanent disfigurement, was considered a mark of femininity, status, and beauty.

The practice, known as "foot binding" or "lotus feet," emerged in imperial China and persisted for almost a thousand years, deeply impacting the lives of countless women. It was a brutal process that involved breaking the toes of young girls and bending them under the foot, creating an unnaturally arched shape. Feet were then tightly bound with cloth bandages, preventing normal growth and resulting in feet that were often just a few inches long. This disfigurement was seen as desirable, particularly among the upper classes.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Origin | Imperial China |

| Duration | Approximately 1,000 years |

| Purpose | Aesthetic ideal of beauty, social status, increased marriage prospects |

| Process | Breaking toes, arching the foot, and tightly binding with bandages. |

| Consequences | Severe pain, mobility impairment, lifelong health issues, societal limitations. |

| Symbolism | Femininity, elite status, control over women. |

| Peak Period | Manchu Dynasty, symbolized by Empress Cixi. |

| Decline | Late Qing Dynasty, and especially after the introduction of high heeled shoes. |

| Legacy | A stark reminder of cultural practices that prioritize ideals over individual well-being. |

For a detailed overview, you can refer to the Encyclopedia Britannica.

The arch was shoved up to make the foot shorter, and the other toes were bent under the ball. In many cases, the arch was broken. The goal was to create a "lotus foot," a small, arched foot considered exquisitely beautiful. This ideal, however, came at an immense cost.

The impact on a person's foot was devastating. The four smaller toes were tucked underneath, pulled towards the heel, and wrapped with bandages. The arch was intentionally broken to create a more pronounced curve. The resulting feet were often deformed, making walking excruciatingly painful and mobility severely limited. Women with bound feet were often entirely dependent on others, reinforcing a patriarchal societal structure where their value was tied to their confinement.

The process began when girls were very young, sometimes as early as age four or five. The feet were soaked in hot water, and the toenails were trimmed short to prevent them from growing inward. The toes were then broken and bent under the sole of the foot. The foot was tightly bound with bandages, creating an unnatural shape and preventing further growth. The binding had to be constantly adjusted and re-wrapped to maintain the desired shape, a process that caused chronic pain and increased the risk of infection. The severity of the binding varied, with wealthier families often binding more tightly to achieve a more pronounced "lotus foot."

- Renee Rapp Nudes

- Crystal Lust Social Media

- Lure Hsu Age 2025

- How Did Bruce Lees Son Die

- Boosie Fade Latest

Chinese foot binding, a practice of deforming women's feet by breaking and binding them tightly, emerged in imperial China. It gained cultural significance in the Manchu Dynasty, symbolized by Empress Cixi. The process involved breaking feet to minimize size, creating an aesthetic ideal of beauty. Despite its social implications and medical consequences, foot binding was depicted in literature. Women were often praised for their delicate movements and dainty appearance, as entranced emperor li yu by dancing on her toes.

So, foot binding was a way for families to increase the odds of their daughters marrying well. But other historians have also argued that foot binding meant that the women would be entirely dependant on their fathers and husbands, and thus that it was a way of controlling women. It was a way to make sure young girls sat still and helped make goods like yarn, cloth, mats, shoes and fishing nets. The practice became increasingly common among all social classes, although the degree of binding and the size of the foot varied.

The rationale behind foot binding was complex and multifaceted. It was seen as a status symbol, particularly for women of the elite, indicating that they did not need to perform manual labor. It was believed that tiny feet enhanced a womans attractiveness, making her more desirable and increasing her marriage prospects. The practice was also enforced by men and by a societal desire to restrict women's mobility. Foot binding was a way to control women and to keep them confined to the home. By limiting their mobility, women were less able to participate in activities outside the domestic sphere.

Wang Lifen was just 7 years old when her mother started binding her feet: breaking her toes and binding them underneath the sole of the foot with bandages. After her mother died, Wang carried on. From then on not just courtesans and concubines but even simple housewives and farmwomen would bind their feet. The physical pain was a constant companion, but the cultural pressure to conform was even stronger.

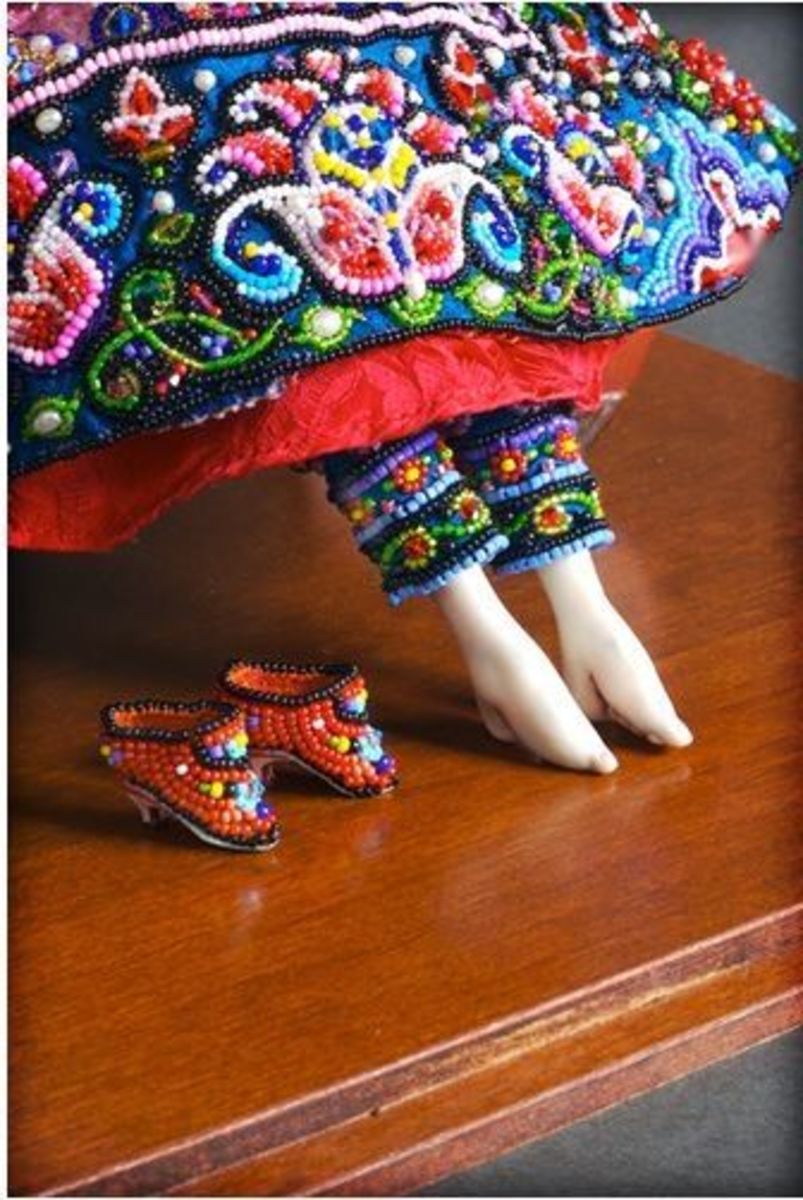

Feet altered by foot binding were known as lotus feet and the shoes made for them were known as lotus shoes. The association of small feet with beauty and social standing became deeply ingrained in Chinese culture. Lotus feet were seen as delicate and feminine, and women with them were often considered graceful and desirable. This aesthetic ideal persisted for centuries, influencing fashion, art, and literature.

The practice wasn't solely about aesthetics. Historians have argued that foot binding was a form of social control, a way to restrict women's freedom and ensure their dependence on men. By limiting mobility, women were confined to the domestic sphere, making them easier to control. The practice also had economic implications. Women with bound feet were less likely to work outside the home, contributing to a system where they were dependent on their fathers and husbands for support.

Chnz, or footbinding, was the Chinese custom of breaking and tightly binding the feet of young girls to change their shape and size. The process involved breaking the bones of the foot, bending the toes under the sole, and binding the foot tightly with cloth. The goal was to create a small, arched foot, known as a "lotus foot," considered beautiful and a sign of status. The practice began in the imperial court, but gradually spread to all social classes. The impact on women's lives was profound, severely restricting their mobility and contributing to chronic pain and health problems. The practice also reinforced patriarchal control, as women with bound feet were more dependent on men. Foot binding gradually ceased in the early 20th century due to its health impacts and changing social values.

Once their rule was over, life in China changed dramatically, and many ancient traditions. The impact can be appreciated by considering three of Chinas greatest female figures. The strap of a straw sandal or geta (a platform wooden sandal) runs through the gap.

The article below and others like it talking about foot binding keeps referring to some bizarre fetish article. Frauen mit abgebundenen Fen, um 1910 normaler und abgebundener Fu. Das Fuebinden war ein bis ins 20. Jahrhundert in China verbreiteter Brauch, bei dem die Fe von kleinen Mdchen durch Knochenbrechen und anschlieendes extremes Abbinden irreparabel deformiert wurden. The most shocking aspect of foot binding, beyond the horrific images of actual bound feet, is the devotion Chinese women had to continuing the practice that hobbled thousands of girls. Comparable to the tiny waist created by the corset and adored by Europe, the Chinese revered a tiny foot.

The practice, however, wasn't universally embraced, and voices of dissent existed throughout its history. Critics argued that the practice was cruel and unnecessary, causing immense suffering. Some women resisted the practice, while others questioned its value and impact on their lives. The debate surrounding foot binding highlights the complexities of cultural traditions and the importance of considering their effects on individuals, particularly women.

Rntgenbild av bundna ftter jmfrelse mellan en kvinna med naturliga ftter (vnster) och en kvinna med bundna ftter. Fotbindning, ven lotusftter eller liljeftter, r en gammal kinesisk sed som gick ut p att bryta snder och binda unga flickors ftter fr att minska deras storlek genom att deformera dem. Photographer and academic Jo Farrell has spent over a decade painstakingly documenting women of China who have had their foot bound. The commitment to the practice, despite its inherent suffering, is a testament to the power of cultural ideals and the challenges of challenging deeply ingrained traditions.

By the 1940s, when high-heeled shoes became available to the poor, foot binding was virtually gone. This decline was due to the rising influence of western ideas, which promoted women's rights and questioned practices that restricted their physical freedom. The practice had gradually ceased. The introduction of high-heeled shoes, which mimicked the appearance of lotus feet, also played a role in its demise, as women could achieve a similar aesthetic without the pain and suffering of foot binding.

The legacy of foot binding serves as a powerful reminder of the historical treatment of women and the complex interplay between culture, beauty, and suffering. It compels us to reflect on the ideals we embrace and the costs we are willing to bear in their pursuit. It underscores the significance of questioning traditions and promoting individual well-being over societal pressures.

Article Recommendations

- Jack Quaid Girlfriend

- Sone385

- Tattoos On Elderly People

- Courtney Richards

- Why Didnt Bob Marley Get Treatment

Detail Author:

- Name : Mr. Donavon Mayert

- Username : hartmann.alivia

- Email : alva16@morar.com

- Birthdate : 1978-01-22

- Address : 559 Koss Circle Suite 953 South Silashaven, GA 23738

- Phone : +1-757-223-5674

- Company : Feest and Sons

- Job : Construction Driller

- Bio : Cumque ipsa ut consequuntur dignissimos quia et. Eum nesciunt suscipit enim culpa qui omnis corporis officia. Doloribus nam vel dolorum voluptatibus esse quis non. Autem qui ut et.

Socials

tiktok:

- url : https://tiktok.com/@kay.douglas

- username : kay.douglas

- bio : Ut quo quasi non aut rerum architecto. Et et et et sit veritatis.

- followers : 4761

- following : 438

facebook:

- url : https://facebook.com/douglask

- username : douglask

- bio : Deserunt et temporibus et facilis iusto a iure.

- followers : 500

- following : 729